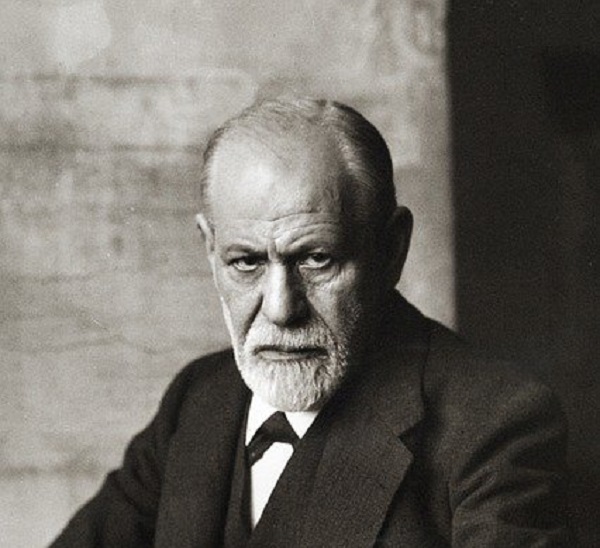

Dr Sigmund Freud, MD, the Wizard of Dreams, thought of society as composed of rules from within. Of rules meant to subdue the tides of emotional excess that surge too freely within. He also believed that contentment arises from attuning one’s life with one’s true feelings.

Dr Freud, the plumber of the unconscious, not only focused on the vitality of self-awareness as being fundamental to psychological insight, he also thought of the emotional brain as being full of symbolic meaning — the interaction of metaphors, stories, myths, and the arts.

Interestingly, Dr Freud’s antipathy towards religion was, in more ways than one, legendary, albeit he often referred to the experience of nirvana as the ‘awful depths’ of Eastern thought in metrical terms. His perspective, arguably, leaves too little space for descriptions that show the positive contributions of spirituality in child development. What’s more, new research has clearly demonstrated children’s capacity for profound religious thought. But, this does not digress from Dr Freud’s signal contribution to his celebrated theory of conscience: of how it is formed out of primitive fears, which is also contiguous with his brilliant analyses of the human instinct, and the concept of character, or the self — from infancy to maturity.

Vital Wish

Dr Freud believed that dreams represent the unconscious trying to express itself consciously. He scored his first colossal triumph by way of his magnum opus, The Interpretation of Dreams, published at the turn of the last century. It is a work that makes up the unconscious mental life as the vital wish that lies there unfulfilled, striving for fulfilment against external demands. It explores Freud’s universal manifestation of the psychic activity underneath the ordinary, recognised conscious activity — a doctrine that was engineered to energise the summit of his thought, sooner than later.

What makes Dr Freud’s work unique is the reader finds oneself in a world of dreams. Of the existence of dreams for the importance and sense of it, including the elements of wish-fulfilment brought through the objective of realisation, or reduplication — or, what Dr Freud called dream work.

In its totality, Freud’s study of dreams also led him directly into the practical applications of psychoanalysis as a tool for neuroses. It elevated his acumen to unlock the difficulties and perplexities of the hidden side of human nature — a clear path into what makes the unconscious mental life a subject to the action of the mechanisms which are not explicable by the means at hand, or ordinary rationalised thinking. His expansive book balanced the domain that went beyond all negations with the unconscious. It also set the ball rolling, while beginning to ‘read’ Freud’s own emerging conception of the psyche into a more elementary, psychological concern.

Paradigm Shift

With his introduction of the id, the superego, and their problem-child, the ego, Dr Freud advanced scientific comprehension of the mind infinitely. In so doing, he ripped ‘open’ motivations that are normally imperceptible to our consciousness. While there’s no question that his own prejudices and neuroses influenced his observations, the components are less consequential than his ‘paradigm shift’ as a whole.

That he went overboard with some of his theories is part of history, yes; yet, his path-breaking work on dreams catapulted the genius in him to embark on his scholarly march. Though the first edition of his book sold only a few hundred copies, Dr Freud’s ideas began to spread, first in Austria, and then abroad. Within a decade, the big word of Freud’s amazing insights had spread to the US. It did not take long, thereafter, for his ideas to be espoused in medical and academic circles worldwide.

Dr Freud ‘meditated’ upon others’ minds as much as he did his own. He believed it was conceivable to lay bare the content of the unconscious if one paid attention to such normal behaviours as jokes, slips of the tongue, free associations and — most importantly — dreams.

Convinced of its import, Freud is also reported to have quipped that a marble tablet, on his home, would one day read: “Here, on July 24, 1895, the secret of the dream revealed itself to Dr Sigm Freud.”

Dreams are surely made of such stuff. In this case, the pith was Freud, and the staff was his dream — one that peered deeply into his own psyche and into that of all human beings.

The Interpretation Of Dreams

Dr Sigmund Freud MD

First Published in 1900

Om Books [2019]

pp 674

Price: ₹273.00