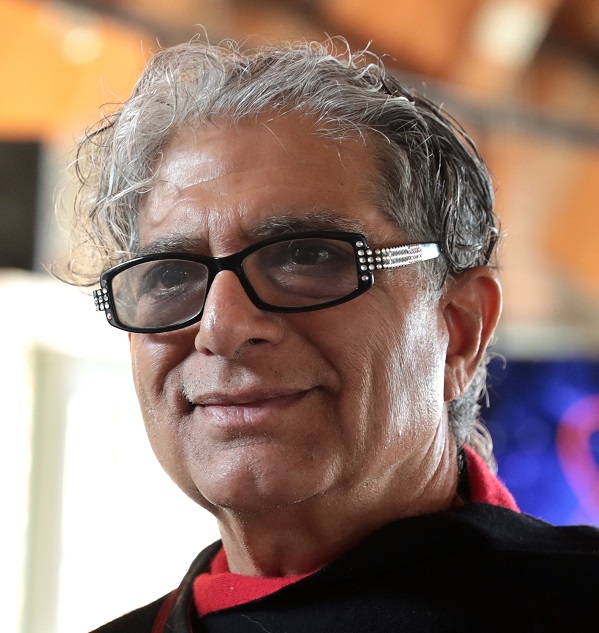

Contemporary self-help teachings are attractive because they assure us that we are the makers of our own destiny. They preach that we have within us the power to change our lives for the better, even to make ourselves anew. Self-help leaders, from Tony Robbins to spiritual gurus like Robin Sharma and Deepak Chopra, ask us to take responsibility for our lives.

The idea is simple: by taking responsibility for our emotions and what happens to us, we rid ourselves of dependence and thereby potential weakness. By accepting wholeheartedly, the value of personal responsibility we become empowered, for no longer do we allow our lives to be dictated by sheer happenstance, or the unpredictable whims of others.

Personal responsibility is not merely a core value of much self-help. Harvard political scientist, Yascha Mounk, has recently argued, we are today living in The Age of Responsibility. Lauded in presidential speeches as well as bestselling books [like Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules For Life], the value of personal responsibility has become central to contemporary moral and political discourse.

Obsession With Individual Responsibility

Yet this has not always been so. Mounk describes the historical shift from a conception of ‘responsibility-as-duty,’ prior to the 1960s, to a conception of ‘responsibility-as-accountability’ that emerged forcefully during the tenures of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. This has since become common sense.

In the wake of the ‘neoliberal turn,’ collective responsibility was exchanged for a myopic obsession with encouraging individuals to become self-sufficient.

This shift in the meaning of responsibility has redirected attention from wider structural transformations to the actions of individuals and, in the process, led to the scaling back of the Welfare State. Thus, welfare regimes have been under siege since the ‘eighties.

The ‘responsibility framework’ changed the meaning of the Welfare State: once conceived as a public institution based on multiple values, it is now regarded as a mere instrument designed to reward the responsible and punish the irresponsible.

This perspective casts the popularity of self-help teachings in a new [more sinister] light. Deregulation and large cuts to social services have produced dire socio-economic conditions that demand a high degree of personal responsibility just to get by.

Some scholars argue self-help and spiritual teachings offer individuals a message of personal empowerment and are popular only because they are a useful means of coping with the intense precariousness and social insecurity experienced by many today.

We Do Not Lack Agency

One response to the responsibility framework on the part of progressives has been to deny the possibility for personal responsibility. Some egalitarian philosophers and sociologists have countered the rhetoric of responsibility, most commonly invoked by conservatives, with the claim that we are, in fact, wholly by-products of social circumstance: that we lack any agency at all.

This tactic, although understandable, is deeply misguided. The fact that most people on both the Right and the Left accept that personal responsibility is an important value suggests that this strategy is nothing short of political suicide.

In other words, telling ordinary individuals they lack agency is unlikely to be met with enthusiasm, no matter their ideological leanings. Additionally, personal responsibility is central to so much of modern life: democratic institutions, intimate relationships, the rule of law. All of these presuppose the possibility for responsibility.

Indeed, it’s hard to imagine what a society that took seriously the idea that we have no agency whatsoever would look like.

A [Partial] Defence Of Self-Help

Progressives are right in suggesting that too little attention is paid to the role of social structures in determining how people’s lives go. One of the core problems with self-help teachings is that they tend to distract us from the myriad ways that our successes and failures depend on factors beyond our control. We are encouraged to see our lives as self-made, rather than as the by-product of collective efforts and contingencies.

Still, the popularity of self-help cannot be reduced to the insecurity caused by neoliberalism. For one, self-help can be traced back to the Stoics of antiquity. Although certainly modernised, it nevertheless preaches a similar gospel of self-reliance.

Second, self-help empowers people by giving them a sense of agency, the feeling that what they think and do actually matters. To recognise the value of this we need only consider what happens when one is told the opposite: when people believe they lack agency, they generally act accordingly.

Finally, modern life, given the scope of freedom it affords, requires self-regulation. Ask anyone currently on a diet, raising kids, or working on their anger issues whether or not taking responsibility for their emotions and actions is important.

Self-help is both useful [and, sometimes necessary], but it needs to be tempered by a sociological understanding of the reality of social life. Self-help teachings can empower, but they can also convince people they are responsible for their own misfortune when, in fact, they aren’t. In these instances, self-help can become dangerous and destructive.

Self-help does not make for good public policy. It is one thing to take responsibility for our lives, and quite another to punish someone [or, let them be punished by the State] because we think they didn’t do the same.

It is an injustice to the Welfare State to view it as a mere instrument for dolling out rewards to the responsible. It is more than that; it is a public institution meant to embody the values of trust, equality, benevolence, justice, freedom and social solidarity.

If we allow self-help philosophy to inform our approach to public policy, it will shrink our moral imaginations. It will leave us less able to see when it is inappropriate to apply the value of personal responsibility, and also less willing.